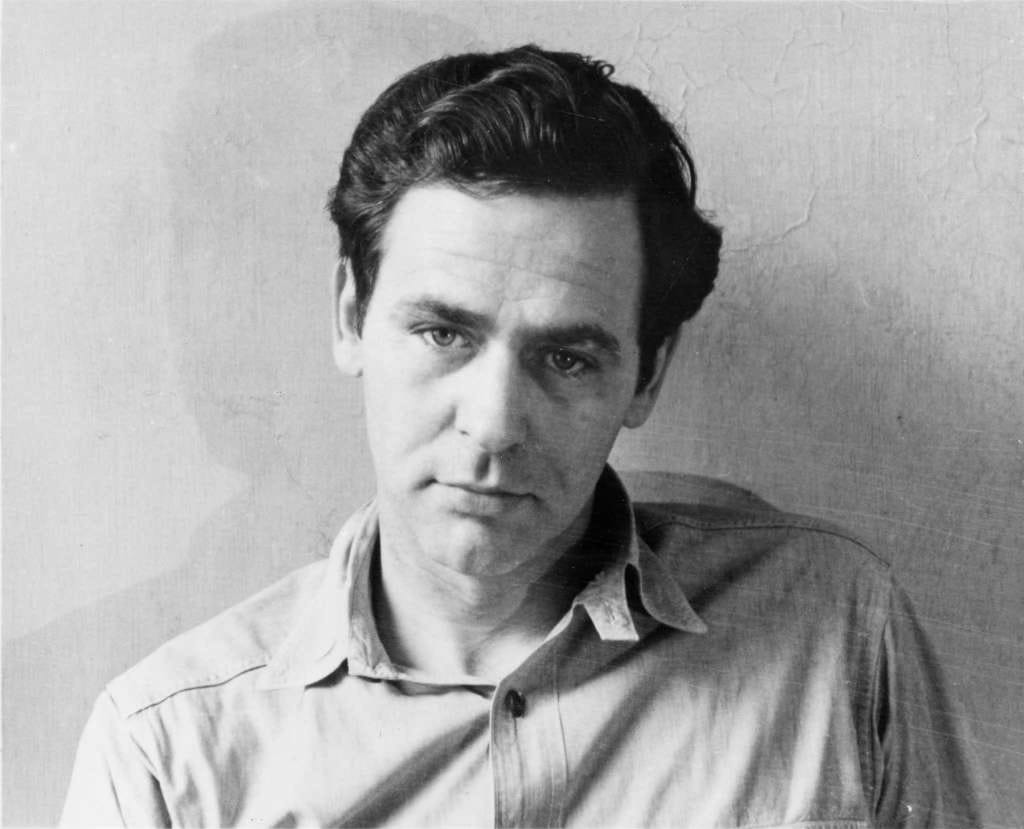

James Agee, the Anarchist Sublime

The Collected Poetry of James Agee was published a few months ago, marking the sixth of a projected nine volumes of his writings. The project, from the University of Tennessee Press, is guided by the unshakeable academic conviction that nothing must be left out. The volumes have coincided with constant drip of studies and reprints. The Library of America devoted a pair of volumes to Agee’s career as a journalist, poet, film critic, essayist, novelist, and screenwriter. Chaplin and Agee told the story of a friendship between the writer and the movie star. Fordham University Press reprinted Agee’s long essay on Brooklyn as a standalone book. Cotton Tenants, edited and shepherded into print by yours truly, threw new light on the development of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee’s best-known book.

The publishing projects have finally put the lie to a complaint, circulating since Agee’s premature death in 1955, that he wasted his talent in drink and depression. Now that the range of his achievement has come into view, it may have been that the variousness of his genres explained his reputation as an underachiever.

Yet there is no biography in print. In fact, no biography has been published since Lawrence Bergreen’s jaundiced 1984 study. Why? Agee died at forty-five, indebted and uninsured. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, his masterpiece with the photographer Walker Evans, was long out of print, along with the rest of his major writings. A Death in the Family, his novel, was incomplete and unpublished. The record of neglect and disappointment, so noticeable to his contemporary critics, somehow continues to hide away the coherence of his literary biography. Agee courted failure deliberately, until it grew into a method. He thought of himself as an anarchist, living in and through a special sensibility. The preamble to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men set forth its first premise:

Every fury on earth has been absorbed in time, as art, or as religion, or as authority in one form or another. The deadliest blow the enemy of the human soul can strike is to do fury honor. Swift, Blake, Beethoven, Christ, Joyce, Kafka, name me a one who has not been thus castrated. Official acceptance is the one unmistakable symptom that salvation is beaten again.

Agee’s fury began on May 18, 1916, the day his father was killed in an automobile accident. He was six, and little in his later life suggests that he recovered from the loss. Between ages ten and fourteen, he lived at St. Andrews, an Episcopal school near Sewannee, Tennessee. The Morning Watch, a novella he composed about this period, took fatherlessness as its leitmotif, once in lamentation for Agee’s missing father, once again in yearning for a spiritual surrogate. Orphaned male writers often want to test the limits of their talent against contrived obstacles. Agee’s fury, though, did not inflame in him a will to power, nor did it nurture in him a sense of victimhood. Of sidelong flashes of anger at his mother, there were many. She had him circumcised at age eight, and, after enrolling him in St. Andrews, she hid her diffidence behind her piety. He expressed his feelings in the lines of a poem:

Mumsy you were so genteel

That you made your son a heel.

Sunnybunch must now reclaim

From the sewerpipe of his shame

Any little coin he can

To reassure him he’s a man.

After leaving St. Andrews, Agee spent one year in Knoxville High School, then went north to Philips Exeter Academy, and afterward, Harvard. Upon graduation in 1932, he went directly from Cambridge to New York to take a staff position at Fortune.

Most writers encompass a wider range of personal experience. At sixteen, Agee traveled to England and France for a bicycle trip with Father Flye, his St. Andrews teacher and mentor. He never returned to Europe. In New York, he associated with actors and writers with temperaments and backgrounds similar to his. He described his work for the Luce publications as a “semisuicide,” but he did not quit until 1948, when he moved to California to write screenplays for John Huston. Soon after he relocated, he suffered a heart attack that foreshortened his collaboration with Huston and ruined his own desire to direct.

“I am essentially an anarchist,” Agee wrote in 1938. He professed his allegiance on numerous occasions and never contradicted himself. In an autobiographical statement in 1942, he referred to himself as an “armchair anarchist.” Two years later, in a profile for Life magazine, he portrayed Huston as “a natural-born antiauthoritarian individualistic libertarian anarchist, without portfolio.” The following year, Agee again allied himself with “the sentiments and ideas of something practically extinct—the old-fashioned, nonviolent anarchist.” This figure he imagined to have been “a warm, generous-hearted, compassionate, angry man who really did love freedom.” All these remarks have been published since 1962. Biographers and critics have made nothing of them. Why the silence?

Ignorance, for one thing. As Dwight Macdonald once pointed out, “Anarchism does not mean ‘chaos’ as the New York Times and most American editorialists think. It just means ‘without a leader.’” Anarchism cultivates political practices independent of the modern power-state and its corporate allies. Rather than vanguardism, it encourages direct, democratic participation. Rather than the formation of establishments, it encourages voluntary associations vitalized by spontaneous effusions and organized around cooperation.

Agee did not join any political party, and voted just once. In holding himself aloof from the factionalism of the midcentury years, he honored his naturally generous temperament. During Charlie Chaplin’s last, raucous press conference in New York, it was Agee, speaking from the rafters, who challenged the anticommunist newspapermen. Then again, his friend Whittaker Chambers showed up late one night at his Greenwich Village apartment, drunk and distraught, and fell asleep on his couch sobbing about the communists.

What little Agee had to say about real politics is enough to make one glad he did not say more. He characterized World War II as “a rattlesnake-skunk choice, with the skunk of course considerably less deadly yet not so desirable around the house that I could back him with any favor.” He wrote a bitter satire on the bombing of Hiroshima, followed by an apocalyptic screenplay for Chaplin on the subject of thermonuclear holocaust. It was possible to support the war and condemn the bomb, and the stance could arise from mutually supporting moral and political convictions. In 1943, Agee recorded his pessimism for the coming postwar order: “I expect the worst of us and of the English; something so little better in most respects (if we get our way) than Hitler would bring, that the death of a single man is a disgrace between the two.”

If the political content of anarchism exhausted its significance, then it might merit nothing more than a footnote in Agee’s biography. But this is not so. More than an attitude, less than a creed, anarchism was to Agee a loosely worn skirt to defend the creativity of perception against the metaphysics of the concept and its embodiment in the specialist system, by which experience was isolated, desiccated, and vitiated. As he wrote in 1950:

Allegiance to ‘the modern mind’ must have deprived countless intellectuals of most of their being. Certainly among many I have known or read, feeling and intuition are suspect, sensation is isolated, only the thinking faculty is thoroughly respected; the chances of interplay among these faculties, and of mutual discipline and fertilization, are reduced to a minimum.

A number of American writers voiced similar sentiments after the 1930s and before the 1960s, though their history remains to be written. The leading narrative follows the journey of the mid-century avant-garde from Marxism to neoconservatism and registers the prepossessing influence of European literature and philosophy. But there is another story, a return from European metaphysics to the indigenous temper of anarchism.

This story is laid away in letters, diaries, interviews, and biographies. Edward Abbey rebelled against his father’s Marxism and tried to write “A General Theory of Anarchism” throughout the 1950s before settling on “Anarchism and the Morality of Violence” for his master’s thesis in philosophy, filed at the University of New Mexico in 1959. Dwight Macdonald resigned his Marxism in the 1940s and began calling himself a “conservative anarchist.” Paul Goodman introduced himself as “an old-fashioned anarchist” while C. Wright Mills wrote, a few months after publishing The Power Elite in 1956, “What these jokers—all of them—don’t realize is that way down deep and systematically I’m a goddamn anarchist.”

Robert Lowell, writing to Flannery O’Connor in 1954, noted that “Henry Adams called himself a conservative, Catholic anarchist; I would take this for myself, only adding agnostic.” Lowell, like Agee, was packed off to an Episcopal boarding school as a youth. He, too, found himself in the grip of the “idealistic unreal morality and the insipid blackness of the Episcopalian church.”

Here is a clue to the ethical value of anarchism. “I feel bound to be an anarchist in religion as well as ‘politics,’” Agee wrote in 1938, contending that “the effort toward good in both is identical, and that a man who wants and intends good cannot afford to have the slightest respect for that which is willing to accept it as it is, or to be pleased with a ‘successful’ compromise.”

Agee discovered the “effort toward good” from Father James Harold Flye, who joined the history faculty at St. Andrews one year before he arrived and served as his moral tutor thereafter. The inheritance weighed heavily on him. At Phillips Exeter, where his desire to write awakened, then again at Harvard, he offered public displays of his piety. In 1934, when his first book of poems was published, the volume seemed to his friend Robert Fitzgerald “the work of a desperate Christian.”

Even after his despair lifted and his belief scattered, his voice retained a religious penumbra. In 1950, he participated in a Partisan Review symposium: “Religion and the Intellectuals.” How, he asked in his contribution, could secular intellectuals mock the idea of transubstantiation while they accredited the idea of penis envy? He continued:

It is fashionable to feel and to force upon others, an acute sense of social responsibility; but it is rare to find a non-religious person who recognizes what is meant by sinning against oneself, or who recognizes that, granting extenuating circumstances, every person is crucially responsible for his thoughts and actions.

Solicitude for Father Flye coincided with Agee’s scorn for churches, vestments, and hierocracies. The Reverend Harry Powell, the murdering preacher in The Night of the Hunter (1955—Agee cowrote the screenplay) bears the sublimated terror of his devotionals at St. Andrews.

The script for Chaplin, The Tramp’s New World, abounds in anticlerical attitudes. Then there is Father Jackson in A Death in the Family, Agee’s novel about the automobile crash that killed his father. Two-thirds of the way through, he juxtaposes a remarkable pair of scenes. In the first, Mary, alone in her room after news of her husband’s accident reaches her, pleads with her God to tell her why this horrible event has befallen her. In the next scene, Rufus encounters a crew of older boys from the neighborhood. They ask him to dance for their pleasure. Suspicious that they are tricking him, yet desperate to win their approval, his moral perplexity mirrors his mother’s. The juxtaposition poses the problem of theodicy, the traditional jurisdiction of priests and theologians, but Agee refused to allow Father Jackson an un-contradicted answer.

“I tell you Rufus, it’s enough to make a man puke up his soul [says Mary’s brother, Andrew, at the end of the novel]. That—that butterfly has got more of God in him than Jackson will ever see for the rest of eternity. Priggish, meanly-mouthed son of a bitch.”

The Night of the Hunter and A Death in the Family use the undivided intuitions of children to point out that ecclesiastical guardianship over morality rests on false riddles and trumped-up antagonisms. The film, written from the perspective of two children, shows the Reverend Powell (played by Robert Mitchum) with “Love” tattooed on the knuckles of one hand, and “Hate” on the other. In the novel, the last word is given to Rufus (the young Agee) as he puzzles over his uncle Andrew’s outburst. Andrew had directed the outburst toward the family as well as Father Jackson. Rufus wonders why:

He hates them just like opening a furnace door but he doesn’t want them to know it. He doesn’t want them to know it because he doesn’t want to hurt their feelings. He doesn’t want them to know it because he knows they love him and think he loves them. He doesn’t want them to know it because he loves them. But how can he love them if he hates them so? How can he hate them if he loves them? Is he mad at them because they can say their prayers and he doesn’t? He could if he wanted to, why doesn’t he? Because he hates prayers. And them too for saying them. He wished he could ask his uncle, “Why do you hate Mama?” but he was afraid to.

The ethical dimension of Agee’s anarchism entailed the same double-sided consequences as his anti-politics. He cast off the superintending influence of religious dogma, and rejected its metaphysics of good and evil, on the assumption that “every person is crucially responsible for his thoughts and actions.” The liability of this utopian attitude toward personal responsibility was tumult omnipresent, a ceaseless struggle against the poison of ambivalence. An emotional life divested of the metaphysical confidence of religious morality stands undefended before passion’s caprice, as Agee demonstrated in deciding to write a love letter to his ex-wife, Alma.

He decided to write to Alma (as he explained in the letter) after Helen Levitt showed him a photograph she had taken of them when they were married, “and seeing it, fourteen years dropped out from under me, and I knew just where we were then, and where we really belong, and where we always ought to be. I am still in love with you, Alma” The background is important. Alma Mailman had fallen for Agee when he was still married to her friend Olivia Saunders, the favorite daughter of a prominent New York family. To punish Alma for the affair, the Saunders family shunned her. In her own family, only her father did not break ties. Marrying Agee washed away part of the stain. Then disaster struck. Less than one month after Alma gave birth to their child, Agee confessed that he had been sleeping with Mia Fritsch, a researcher at Fortune. Alma boarded a freighter to Mexico.

When he wrote the letter beckoning Alma to return, he was forty-three. He had a third wife (Mia) and two children under his care. Alma, forty years old, had remarried as well, also with two children. The letter proposed, in effect, that they do it all over again, that they smash up two families and begin anew. All because he got a glimpse of an old photograph.

An autobiographical statement confessed the vulnerability behind the immorality: “he is pronouncedly schizoid, and a manic-depressive as well, with an occasional twinkle of paranoia.” Others saw Agee as he saw himself: the children who chalked on the steps of his home in Brooklyn, “The Man Who Lives Here is a Loony”; and Thomas Wolfe, who reported, after a long evening of conversation, that Agee was “crazy,” that he “was always talking about things in spirals and on planes and things.” A colleague at Time, overhearing a drunken Agee cursing a telephone operator, was moved to say that “a wild yearning violence beat in his blood, certainly, as just as certainly, the steadier pulse of a saint.”

Lionel Trilling found the necessary distinctions. During the last conversation he had with Agee, they talked about the concept of ambivalence in Freud’s The Ego and the Id: loving and hating at the same time. Agee said it disgusted him. “It seemed to me then,” Trilling wrote, “that his brilliant intensities of perception and his superb rhetoric required him to affirm, if not actually to believe, that the human soul could exist in a state of radical innocence which was untouched by any contrary.”

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men bore James Agee’s most conspicuous traits: his oscillating voice, perpetually prepared for paralysis; his dislike of ordinary politics; his determination to cut his perceptions down to the bone of innocence; his struggle to find a place to stand in a ruined world.

The background is well known. In 1936, Fortune sent Agee and the photographer Walker Evans to Alabama. They were to file a report on conditions in tenant farming. Agee and Evans lived briefly with three impoverished families. The following year, Agee rented a house with Alma in Frenchtown, New Jersey, and set to work. He wrote in pencil, at night, breaking his concentration to read passages aloud to Alma and to confer with Evans and Dwight Macdonald, Robert Fitzgerald, and Delmore Schwartz. It was in Frenchtown in 1938 that he wrote the letter to Father Flye in which he first called himself an anarchist.

Concern for the plight of Southern farmers had not been so active since the 1890s. Twenty-seven years old, Agee was running strong in his talent. Yet he squandered his chance to make himself heard. The book added little, if anything, to the general stock of ideas about tenant farming. Long patches of the prose were opaque. Fortune rejected the initial essay; the publisher deferred the book after arguing with the authors. By the time it appeared, in 1941, the war held a monopoly of national concern. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men sold about six hundred copies in its first year, a few thousand more in remainder, and quietly went out of print. Trilling said he rarely heard anybody mention it in the 1940s and 1950s, not even in private conversation.

Agee went out of his way to fend off the sympathies of his readers. In the preamble he copied out the famous final sentences of The Communist Manifesto, but then added, in a note to “the average reader,” that “these words are quoted here to mislead those who will be misled by them.” In fact, “neither these words nor the authors are the property of any political party, faith, or faction.” Agee knew enough about politics to understand the economic and social forces buffeting the lives of the sharecroppers. He understood, as they could not, the real calamity of their situation. Yet he rejected the meliorism of the liberal reformers as firmly as he rejected the radicalism of the communists:

This particular subject of tenantry is becoming more and more stylish as a focus of “reform,” and in view of the people who will suffer and be betrayed at the hands of such “reformers,” there could never be enough effort to pry their eyes open even a little wider.

The surrealist movement had made its way from Paris to New York in the 1930s. A decade later, the New Fiction matured in the United States, spurred by translations of Kafka and Kierkegaard. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men could have been taken up as an example of experimental writing, if Agee had not choked off an aesthetic interpretation as well. “It is funny if I am a surrealist,” he wrote in his journal in January 1938. This moment of bemusement soured in the book’s preamble. “Above all else: in God’s name don’t think of it as Art,” he admonished.

There remained the possibility that Agee would appeal to the conscience of his readers. But the preamble resembled the opening pages of Old Goriot, in which Balzac bemoaned the bourgeois turn toward spectatorship in the presence of human pain. “Their hearts are momentarily touched,” Balzac wrote, “but the impression made on them is fleeting, it vanishes as quickly as a delicious fruit melts in the mouth.” Agee likewise supposed that his “average reader” would be edified, nothing more, by his portraits of suffering. Scorning “your safe world,” he borrowed the title of his book fromEcclesiasticus. The irony came at the expense of his readers.

The failing of the book was the main condition of its achievement. Agee intended it as “an effort in human actuality.” Only by antagonizing ready-made techniques of observation did he believe that he could hope to respect, understand, contemplate, and love the sharecroppers as human beings. These were the positive dimensions of his mistrust of inherited forms of cultural authority. He went to Alabama to tell what it was like to be in the presence of a group of undefended, unfamiliar people located on the margins of society. Rather than delineating a problem or an issue, rather than shading his observations into a logic of narrative, he wove a mosaic of braided perceptions, luminous and radiant. In describing a bed, or a pair of trousers, he illuminated the image as if he was bringing it forth for the first time as it had existed always.

To grasp the complexity of this aspiration, consider the conventions dishonored in the execution. Agee did not try to discover new knowledge about his subjects, like a social scientist. He did not present himself as spokesman, overflowing with humanitarian concern, or as a psychologist, building up case histories, or as an ideologist, advancing a science of concepts, or as an artist, falsifying reality in order to reenter selected aspects, or as a professional writer, extracting from his subject a set of techniques. These refusals, and the integrity and responsibility upon which they rested, released a flow of emotional and imaginative energy that transcended the impersonal networks of communication dominating Serious Literature in the United States. Few writers anywhere have applied a greater intensity or sophistication to the involutions of thought and feeling disarmed. Few have been so overwhelmed in the task. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men never found an encompassing vision. Agee presented his struggle to see with a grace and fury all his own.

To forge a Concept out of this impulse to fail, then, would rob anarchism of its essential qualities. For a long time now, the human sciences and their philosophical allies have emphasized the sovereignty of language over experience, have made thought and feeling intelligible as the interplay of text and context. But language may meet an impulse it reflects or constructs only by injuring. Silence dissolves when words bespeak it. Privacy scrutinized in public is no longer privacy. The meaning of dreaming lies in the forgetting. No genuine history of dreaming is possible, for its remembered experience, its forms, interpretations, and stigmata, constitute a loss of its reality.

So it goes with anarchism, whose first principle acknowledges no first principles and whose success depends on consciousness of its inadequacies. It entails a receding horizon, a failing struggle against the trappings of institutions and ideologies. Not demonstration, explanation, and justification, but illumination lies at its center of its aspiration. Absurdity has been its recurring conclusion; satire its method, not merely for criticizing but profaning authority. The “zoological types” exemplified in Balzac’s Human Comedy have shaped many of its impressions and images.

Typically, anarchist poets and writers do not agree on the name of its special source of energy. Agee named it “being” and “fury.” E.E. Cummings named it “Is.” Laura Riding named it “individual-unreal” and warned, in Anarchism is Not Enough, not to dilute it by analogy. That anarchism’s source is hived in a preconscious region of the psyche, undiscoverable by language and hence ungovernable by reflective intelligence; on this essential point, they seem to agree. Standing for the limits of knowing in an Age of Information, anarchism reports itself in maxims, epigrams, and aphorisms, by way of pamphlets and manifestos, when it reports itself at all. (“If I weren’t an anarchist I would probably be a left-wing conservative,” Agee wrote to Father Flye, “though I write even the words with superstitious dread.”) Provocative and enigmatic, exiled and omnipresent, it is the tramp in the ghetto of mass culture.

Anarchism hides in history, while ideologies cotton to institutions. The origins of the modern ideologies lie in a counter-intuitive discovery: man-made institutions may acquire an independent logic, which may turn to confront its makers. In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith put this discovery to work for liberalism, much as Karl Marx, in Capital, made communism answer “a social process that goes on behind the backs of the producers.” Smith’s mystical appeal to an “invisible hand,” like Marx’s attempt to master the “anarchy of production,” whipped history and human nature into a logic of relations. As liberalism and Marxism developed, their ideological vanguards transformed the logic of relations into the science of concepts, built institutions to anchor the Enlightenment, and thereby reproduced themselves in the Association, Bureau, Center, Department, Institute, Office, Party, and University. Therein the intellectuals accumulate conceptual knowledge, score points against the adversary, diagnose crises, uncover scandals, and chronicle their own changing role in the Progress of History

Agee wrote often about the power of film and photography to transcend inherited vocabularies of representation. He reported his fidelity to anarchism fitfully, in fragments and outlines which may give the impression that it is chaotic, or merely eccentric. One such fragment, “Now as Awareness,” ruminated on the necessity of “valuing life above art.” The preamble to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, setting the furies of creativity against the authority of art, religion, history, and society, bore a silent debt to Rousseau, whose “Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts” (1750) voiced the same idea in very nearly the same words: “Our souls have been corrupted in proportion as our sciences and our arts have advanced toward perfection.” William Blake, another of the “unpaid agitators” accompanying Agee to Alabama, echoed the idea in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.”

Anarchism, so understood, substitutes for the process theory of history the ancient aphorism, “History is philosophy by example.” It entrusts itself to a genealogy of spiritual striving. Not invisible processes, but feats of virtuosity renew it. Not a vanguard of intellectuals, but the annals of biography transmit it between the lines of history. Not ideology, but filiopiety. “Those works which I most deeply respect have about them a firm quality of the superhuman,” Agee wrote, “in part because they refuse to define and limit and crutch, or admit themselves as human.”

Marxists and liberals apply ideological and political tests to police their communities. Anarchists appear as isolated stars in a common constellation. Of Jesus Christ, William Blake, Jonathan Swift, James Joyce, Franz Kafka, and Ludwig von Beethoven, Agee said:

Some you ‘study’ and learn from; some corroborate you; some ‘stimulate’ you; some are gods; some are brothers, much closer than colleagues or gods; some choke the heart out of you and make you dubious of ever reading or looking at work again: but in general, you know yourself to be at least by knowledge and feeling, of and among these, a member in a race which is much superior to any organization or Group or Movement or Affiliation, and the bloody enemy of all such, no matter what their ‘sincerity,’ ‘honesty,’ or ‘good intentions.’

By such examples and encounters, he laid up ethical and aesthetic equivalents to the anarchist’s characteristic political gesture in the “propaganda of the deed.”

The critical and commercial failure of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men Agee accepted without protest. No missives to his publisher; no carping about the critics who misunderstood his meaning; no bitterness toward the public who ignored his book. To his failing health he applied another kind of diffidence In the spring of 1955, he was enduring five or six minor heart attacks every day, swallowing nitroglycerine tablets one after another. On May 11, he mailed his last letter to Father Flye: “Nothing much to report. I feel, in general, as if I were dying: a terrible slowing-down, in all ways, above all in relation to work.” Five days later he died in a taxicab on his way to the doctor’s office.

Agee’s success began soon afterward. A Death in the Family won a Pulitzer Prize in 1958. Two years later, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was republished to universal acclaim. Film critics, civil rights activists, and bohemian poets avidly read Agee on Film (1958), Letters of James Agee to Father Flye (1962), The Collected Short Prose of James Agee (1968), The Collected Poems of James Agee (1968), and Remembering James Agee (1974). The introduction to the republication of The Morning Watch compared him to Shelley. He became a legend, a cultural hero for a generation in love with cultural heroes.

All along Agee’s distinction rested with a fraternity of sympathetic writers, “members,” he might have agreed, “of a race which is much superior to any organization or Group or Movement.” C. Wright Mills praised Let Us Now Praise Famous Men for “the enormity of the self-chosen task” and dubbed it “sociological poetry.” Paul Goodman thought “many of the items are presented with extraordinary beauty and power and a kind of isolated truth” and lauded Agee for his “misgivings at being a spy and a stranger, his refusal to submit to the categories of sociology or the devices of drama.” “I feel sure this is a great book,” said Lionel Trilling; “nine out of every ten pages are superb. Agee has a sensibility so precise, so unremitting, that it is sometimes appalling.” Alfred Kazin called A Death in the Family “an utterly individual and original book, and it is the work of a writer whose power with English words can make you gasp.” Robert Lowell said, “I add Agee’s death to his hero’s and can’t forget the epitaph.” But Dwight Macdonald left the finest comment on the whole man:

Yes, I was very fond of Agee and I think he was fond of me, too. We liked each other very much and we respected each other, which is perhaps equally important, you know. He was pretty much of a bum in many ways. He didn’t wash very much, his clothes were filthy, and he was very bad sexually, to say the least—you know, a loose liver. And he drank too much and had a lot of faults. But I must say, he’s one of the few people that I’ve ever met that I would consider, without any question, a genius. Like Auden, Eliot, people like that, without any question.

Agee demanded more freedom than most of his contemporaries while expecting to accomplish less than any of them. Measured against the breed of writers who emerged in the 1950s, his prose seems static, as if caught between equally valid perceptions, or immobilized in the bereaved perspective of his boyhood. Unlike the new narcissists, however, he did not exploit his subjects, or betray his ex-wives or his parents for the sake of Art and Ambition. He never forced the grief of his subjects to undergo the brutalities of action or the humiliations of analysis. His oscillating style managed to be realistic and tender at the same time, to get love and death into view rather than sex and violence. As he wrote in his introduction to Walker Evans’s collection of subway photographs, Many Are Called:

Each individual existence is as matchless as a thumbprint or a snowflake. Each wears garments which of themselves are exquisitely subtle uniforms and badges of their being. Each carries in the postures of his body, in his hands, in his face, in the eyes, the signatures of a time and a place in the world upon a creature for whom the name immortal soul is one mild and vulgar metaphor.

Agee confides the dignity of human emotion, and teaches us to detect the false notes in posterity’s trumpets. In this spirit may we remember him; by our furies, rather than by any successes that may be born by them.