Do the People Choose?

An episode in the history of mass communications research

The study was in full swing by June 1945. C. Wright Mills, the field supervisor, was barking assignments to a staff of fifteen interviewers, assistants, and stenographers. Mills had $20,000 to spend, and he did not plan to bring any of it back to New York. He had installed himself and his staff in the Hotel Orlando, in downtown Decatur, Illinois.

A slew of advertisements in the newspapers and on the radio announced the reason. The Bureau of Applied Social Research, from Columbia University, wanted to know how ordinary women made decisions in their everyday lives. Decatur was happy to oblige. About eight hundred volunteers, chosen from a cross-section of the population, sat for thirty-minute interviews. Everybody answered three questions:

Has anybody recently solicited your opinion concerning international, national, or community affairs or news events?

Have you changed your opinion recently about any such events?

Do you know anybody who keeps up with the news, anybody you trust to help you decide your opinion?

The three questions asked—in the same sequence and with varying follow-up questions—covered not only public affairs but also fashions, movies, and brands. The intention was straightforward. Who were the “opinion leaders” in Decatur? The first question yielded a list of self-declared opinion leaders. Here were people who claimed they had been consulted. Answers to the second question yielded another list. Here were people who had influenced the opinions of the women interviewed. The staff took down their names and addresses and went to find them for follow-up interviews.

Answers to question number three yielded a third list, a general list of esteemed people in Decatur. Mills sought out these people himself. He went to see the mayor, visited the bankers, the clergymen, the newspaper publisher, the businessmen big and small. The Bureau’s staff interviewed the eight hundred women in June, again in August, and again in December, each time asking about changes of mind in the interval. At each step, the women, the questions, the subjects, and the answers were broken down into indices of age, sex, income, and occupation and dutifully recorded onto checkbook-sized cards.

Complex in its design, ingenious in its procedures, laborious in its execution, the Decatur study excited a feeling of camaraderie that carried Mills and his staff through the arranging, recording, and coding of approximately 2,000 interviews, all in all. The staff ate dinners together in the Hotel Orlando and enjoyed drinks late into the evening. During the daylight they took opportunities where they found them. As it happened, public opinion in Decatur appeared to be changing over a proposal to build a new section of U.S. highway 36. The staff interviewed 718 women about the proposal, and Mills published the results in a Sunday edition of the Decatur Herald. In eight dramatic days in August, the government dropped two atomic bombs, the Soviet Union entered the Pacific War, and Japan surrendered. Mills wrote and revised questions in a frantic effort to discern the flow of opinion about these events as well. At the end of the month, he reported his progress. “I worry a lot about the whole thing flopping because figures can go screwy, but sometimes it looks like a damn nice little study.”

The plan of the Decatur study originated with the founder and director of the Bureau of Applied Social Research, Paul Lazarsfeld. For an earlier book, The People’s Choice, Lazarsfeld and his collaborators had interviewed a cross-section of voters in Erie County, Ohio, every month for the six months that led up to the 1940 presidential election, and then once more after the election. Those interviews had suggested something Lazarsfeld found intriguing enough to pursue for years afterward. Those voters who had changed their political opinion over the course of the election attributed the change to casual conversations among family and friends to face-to-face interactions, rather than to formal media. Upon this insight, Lazarsfeld mounted his “two-step flow of information” hypothesis. Step one: information came from the formal media. Step two: informal groups or individuals mediated the information for other groups or individuals. Perhaps the technologies of mass communication were not as powerful as the intellectuals believed.

Paul Lazarsfeld held a doctorate in applied mathematics from the University of Vienna, and he thought of himself as a psychologist.5These two dimensions of his biography converged in the approach he made when he went to design his study of opinion leadership in Decatur. Select a sample of ordinary people. Ask a standard set of questions. Codify the answers. Classify the variables. Make the tables. Build an index structure from the tables. Now make the indexes talk to you. In a time before computers, the procedure could be maddeningly complex. But Lazarsfeld believed a well-designed study that employed the correct statistical procedure could pry insights from everyday psychology. If the idea sounded a little like psychoanalysis, that was not a coincidence. Back in Vienna, Lazarsfeld’s mother was trained in individual psychology by Alfred Adler.

The quantitative procedure often raised objections on the part of social theorists. That opinions could be represented by putting a standardized set of questions to a cross-section of a community, that they could be measured on scales of magnitude, and then converted into statistical summations—these assumptions were by no means evident, wrote Robert Merton, a young sociologist at Tulane University, in an essay published in 1940 in the American Sociological Review. Merton’s essay did not mention Lazarsfeld, but it challenged the synonym linking opinion and action as assumed by the style of research toward which Lazarsfeld was moving.

There was another kind of resistance. Lazarsfeld’s “empirical analysis of action” needed manifold resources, not only teams of interviewers, stenographers, and analysts, but offices, data-processing machines, travel and communication equipment, plus a large infusion of money to keep the whole operation going. To organize these tasks, in brief, a new kind of research institute need to be hooked up to a money pump. Foundations, state agencies, and corporations would have to play a role. This Lazarsfeld had known from the beginning. The Vienna Institute, the first of several organizations he founded, had signed as its first client a major chocolate corporation in Germany.

In 1934, while Lazarsfeld visited the United States on a fellowship, the swift political turn in Austria made him a refugee. He had a stint with the National Youth Administration, and another one as director of a research institute at the University of Newark. Then he won a job as director of the Office of Radio Research at Princeton University. When its funder transferred the radio project to Columbia University in 1939, he found himself in New York. The sociology department at Columbia offered him a courtesy appointment, but not much more. Not many officials or professors wanted to be associated with a style of research that relied so heavily on commercial money.

But the success of The People’s Choice and other such studies gained Lazarsfeld growing notice in the United States. During the early 1940s, the radio project analyzed propaganda for the Office of War Information, and began to draw more and more contract work from American corporations. Lazarsfeld renamed the project the Bureau of Applied Social Research. Most important, he hired an associate director, the newly converted Robert Merton, who had joined the Columbia sociology department in 1940.

By 1944, Lazarsfeld was ready to try to go beyond The People’s Choice. If certain people mediated information between media and its consumers, what psychological dynamics might the “two-step flow” hypothesis disclose? In Macfadden Publications, the owner of True Story magazine, he found a client willing to entrust him with $20,000. Because most of the subscribers of True Story were women, Macfadden’s sponsorship would limit the study accordingly. Nonetheless, Lazarsfeld could use the money to trace the actual flow of opinion in politics, fashion, movies, and marketing. He looked at each midwestern city with a population between fifty and eighty thousand. From the sample, he derived thirty-six statistical indicators. He made the number one hundred stand for “most typical.” Decatur, Illinois, scored ninety-nine. All that remained was to find a field supervisor

One day in January 1945, Robert Merton surprised C. Wright Mills with a telephone call. Would he come up from Washington and pay a visit to the new Bureau of Applied Social Research? So far as professional interests went, Merton and Mills had more in common with each other than either man shared with Lazarsfeld. For several years they had engaged in a vigorous correspondence about the sociology of knowledge, crossing pens over matters technical, but agreeing wholeheartedly about the need to develop in the United States what had been a European preoccupation. Merton, having studied with Talcott Parsons, came to the field from reading Emile Durkheim. Mills, having studied with Chicago-trained sociologists at the University of Texas, came to it from John Dewey and George Mead. For the theoretical acuity of their early essays in this emerging field, Merton and Mills were widely considered two of the most promising young sociologists in the country.

There was another, more personal affinity. Unlike Lazarsfeld, who came from a politically prominent, highly educated family in Austria, Merton and Mills were on their own. Merton was born in Philadelphia to immigrant parents—his father worked as a carpenter and storekeeper—and attended Temple University on scholarship. After graduate school at Harvard, and after a brief tenure at Tulane University, he joined Columbia at the age of thirty-one, already considered a leader in the field. Mills was born in Waco, Texas, into a middle-class home. His father was a traveling salesman. When he graduated from high school in Dallas, his father sent him to military school. He transferred to the University of Texas the next year. Like Merton, Mills proved himself in state school, caught the attention of older men in graduate school, and looked upon the expanding field of sociology as a way up and out. Such were the expectations laid up around him, the sociology department at the University of Maryland gave him his first job in 1941 as associate professor, allowing him to leap over the assistant rank completely. And this was before he had finished his dissertation, a sociological history of pragmatism.

On a Friday night in January 1945, Lazarsfeld, Merton, and Mills, three men whose combined work would transform American sociology, met in Manhattan for seven hours. Everything about the evening gave off the scent of possibility. Over a big meal in an expensive restaurant the conversation passed easily over the study, over the city of Decatur, over the moral problems involved in commercial research. Now and then several young women from Smith and Vassar (invited to the table by Lazarsfeld to seduce Mills into joining the team) spoke in sugary voices. After the women departed, Lazarsfeld set forth the terms. Mills was to have the title of research associate at the Bureau. He was to go to Decatur in the summer and direct the opinion study. He could publish under his own name. If all went well, he might expect to join the sociology faculty of Columbia University on a permanent basis. Mills reported the evening in a starry-eyed letter to his parents:

After they had laid out the job and said: “Well that’s it; we want you. Will you come?” I said (holding myself in with bursting joy at the whole idea: christ I’d go for food and shelter) anyway I kept the face immobile and just said: “for how much?” They wouldn’t say, but replied: “You know what you’re worth, name it.” To which little charlie said very quietly, “I won’t charge you that much, but I cdnt think of it in terms less than 4500.” Immediately the guys said “Then your beginning salary will be 5000.” To which the appropriate reply was “That is closer to what I’m worth.” and everybody laughed and felt good.

On January 26, 1945, having secured a leave of absence from Maryland, Mills wrote to Lazarsfeld to accept the offer. Each week that spring, he rode the train from Washington to Manhattan and spent one day at the Bureau, feeling his way around its cavernous offices on 59th and Amsterdam Avenue, getting to know his colleagues, paying visits to friends in the city. Meanwhile, a fight raged uptown. Those opposing the hiring of Mills at Columbia feared that Lazarsfeld and Merton were using him to drive the Bureau closer to the university and its plentiful resources. In this, they were correct. At the end of May, as Mills set out for Decatur, the Bureau signed its first formal agreement with the university.

To detect the “opinion leaders,” the analysis of the data needed to yield clues to three main problems. Could the actual flow of interpersonal influence in Decatur be isolated? Could “opinion leaders” be isolated as a social type? And could the influence be isolated in relation to the class structure of a community? Did the influence flow vertically, up and down class lines, or horizontally, within classes?

Lazarsfeld and his team had not had the chance to interview opinion leaders for The People’s Choice. If there was a singular methodological imperative in the Decatur study, here it rested. To find and talk to the opinion leaders was to isolate the structure and the flow of decision all at once. To isolate the structure and the flow of decision in a typical community would make Macfadden’s advertising department happy, no question. But the implications could not fail to strike up interest among scholars too. Inasmuch as the opinion leader could be isolated at the crossroads of structure and flow, it disclosed the how and the why of decision making. Nobody had attained quite this much insight into the psychology of everyday decision. And no wonder. When Mills went to analyze the data, more than six thousand tables holding as many as ten variables at once spread before him in a river of numbers and symbols. His initial worry about “the whole thing flopping” tightened into acute anxiety.

Could the flow of influence be isolated? Answers to question two (have you recently changed your opinion?) should have yielded the relevant data. Here, the women in the cross-section attested that an opinion flowed from one person to another. Did their testimony mean that the first person could be called an opinion leader, and the second, an opinion follower? The actual answers seemed to require a third category, so that the “opinion leaders” could be said to have given advice; “opinion followers” could be said to have gotten advice; and a third, “opinion relayers,” could be said to have given and gotten. But the design of the study had not anticipated the need for this third category.

Could “opinion leaders” be isolated as a social type? Answers to question one (has anybody recently solicited your opinion?) did give a list of self-elected opinion leaders; whether they could be believed was an open question. The bigger problem was that Mills’s staff had not been able to track down all the people named in questions two and three. And when they did conduct follow-up interviews, they could not always confirm that the influence had transpired.

Could the direction of the influence be isolated in the class structure of the community? Answers to question three (do you know anybody whom you trust to help you decide your opinion?) showed the chain of opinion leadership on politics to be stratified vertically; most of the named people belonged to the top class, with a steady graduation downward. But while the data on politics yielded the best chain of opinion leaders, the data on fashion yielded the best flow of opinion. Mills could not connect opinion leaders in the chain to the same kind of opinion transaction. There appeared to be no way to get them to coincide.

Lazarsfeld flew to Chicago now and then to meet him. There the two men talked about the progress of the study, discussed what they could accomplish with the data. Mills’s ongoing success in other fields, plus Lazarsfeld’s ongoing success in establishing the Bureau, plus the fertility of fresh data, all this, in combination, must have made it easy to hope for the best.

At the end of December 1945, Mills finished the third and final round of interviewing in Decatur. Good news awaited him when he arrived back in New York. Columbia College wanted to keep him on the sociology faculty. In the spring, Lazarsfeld opened up a division of labor research in the Bureau. He hired Mills to run it. Inside of three months Mills made contact with every major union in every major city in the United States and won a contract from the Office of Naval Research besides.

The deadline for the Decatur manuscript came and went. Lazarsfeld paid regular visits to Mills’s apartment in Greenwich Village in 1946. They made some progress. Mills produced approximately three hundred pages of text and put the interviews at the center of a widely noticed article, “The Middle-Classes in Middle-Sized Cities,” published in the American Sociological Review. Lazarsfeld, too, published a widely noticed article based on the interviews, “Audience Research in the Movie Field,” which appeared in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Of the Decatur study, he boasted that it offered “probably the most detailed approach to the movie audience yet undertaken.” Mills’s article relied on data from question three (chain of local political elites) to present a picture of class awareness in Decatur’s social structure. Lazarsfeld, in his article, asked how moviegoers decided, from the fantastic volume of information available in the mass media, which movies to see. “There are people, distributed all over the population” who mediated a “horizontal flow of influence” from person to person, Lazarsfeld wrote. “Actually, it is not too difficult to spot these opinion leaders.”

Mills went to Boston that December to present the dilemmas of the Decatur study to an audience of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He gave a copy of his address to Lazarsfeld, and added two memoranda, in which he explained the “technical tragedy” of the thing. Soon after, he gave another talk about the study, this time at a seminar at Columbia. After he finished, Lazarsfeld rose and remarked, “So that’s what you spent all my money on.”

In the summer 1947, the study was sixteen months overdue. Mills was residing in a cabin in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He wrote to Lazarsfeld to say that he had decided, once and for all, that the tables and equations and figures made no sense. He had the files with him right there in his cabin. He was going to set aside the tabulation machinery and he was going to write the goddamned book then and there. He promised to be back in New York in two months with a completed manuscript in hand. Lazarsfeld fired him.

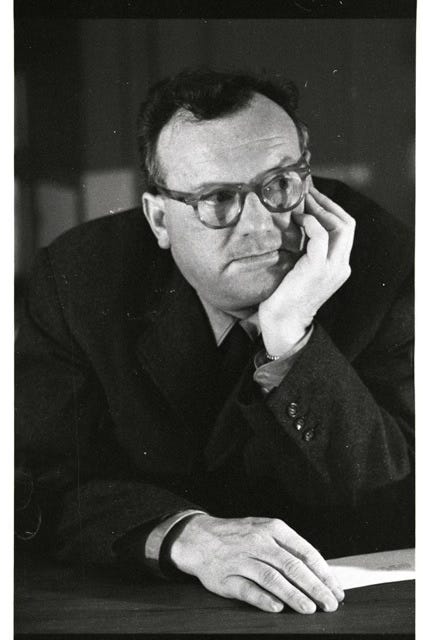

The author interviewed for The Long Road to Decatur: A History of Personal Influence.

For a brief time, Mills’s career at Columbia looked like it might not survive the blow. Since he had been hired to teach in the college in December 1945, he had been prolific. He had a steady stream of material appearing in the magazines and periodicals; he performed contract research for the government; he expanded the labor division of the Bureau; and From Max Weber, the book of translations he published with Hans Gerth, was transforming American social science. In December 1946, Robert Merton warned an inquirer to stay away from his hotshot sociologist. “I can best summarize my opinion of Mills by saying that I regard him as the outstanding sociologist of his age in the country. The tenacity with which I hold this view is indicated by my hope that he will remain at Columbia. It is only fair to say that should be he offered an appointment by the New School, I, for one, shall recommend to Columbia that it do whatever it can to keep him within our Department.” Three months after Lazarsfeld’s action, however, Merton joined with the rest of the department in declining to support Mills’s promotion, citing “deep disappointment over the Decatur episode.”

Mills tried to make amends. When the governor of Puerto Rico asked the Bureau for a study of immigration, he volunteered for the job and carried it out well. He made some headway toward a saving compromise as well. The Decatur manuscript would be divided into two parts, he reported in 1948. Lazarsfeld and two assistants would be responsible for writing one part, and he would be responsible for “theory unburdened by the silly figures.” Given everything, he thought this made “a fine solution and [I] am very pleased with it.” In a second edition of The People’s Choice, published in 1948, Lazarsfeld told readers the Decatur study “will soon appear.” Two years later, however, the project languished. “Paul is giving me a lot of trouble on [the] Decatur manuscript, and the guy who talks for one of us, to the other, has goofed off,” Mills wrote. “God, will I ever get that crap off my desk? It is continually in my hair. I just hate to work on it.”

The Columbia sociology department had hired Merton with the idea that he might mediate such disputes between theorists and empiricists. But the complexities of this dispute defeated even his skills. As he wrote to Mills:

I’ve read every bit of correspondence that’s passed between NY and Reno, and I’m convinced that there’s been a break in communication. Paul hasn’t been able to put what he has to say in a letter, that I know. Perhaps you haven’t either. I know I couldn’t. Having started four or five letters to you, I gave up the thing up as an impossible job.

History has not made the job a whole lot easier. Mills’s manuscript seems not to have survived, so it is difficult to judge how Lazarsfeld and Katz, in publishing the Decatur study as Personal Influence may have solved or ignored the technical dimensions of the dispute as it stood in 1950. It would be foolish for a historian untrained in quantitative research, working with limited evidence, to attempt to adjudicate. Many talented scholars struggled to make sense of the data before Lazarsfeld and Katz made a book of it.

The political dimension of the dispute set another trap. Certainly, it is possible to set Mills’s views on public opinion against the conclusions in Lazarsfeld and Katz. This procedure might expect to find Lazarsfeld and Mills squaring off, the one bemoaning the omnipotence of the mass media, the other proving the sovereignty of the primary group. But Mills’s views on this subject defy paraphrase. In an essay from 1950, for example, he used the Decatur interviews to make the same point made later in Lazarsfeld and Katz. “No view of American public life is realistic that assumes public opinion to be merely the puppet of the mass media. There are strong forces at work among the public that are independent of these media of communication, forces that can and do at times go directly against the opinions promulgated by them.”

How could two men, joined to study the resilience of personal communication, fail so miserably to communicate? One thing is certain. The dispute that started during those first meetings in Chicago, which tangled and deepened in Greenwich Village in 1946, which stole into seminars in Boston and New York, did not end with the publication of Personal Influence. Mills did not get the Decatur material off his desk or out of his hair. He folded away the interviews into the book that made him famous outside professional sociology, White Collar. Later, he made them the basis of “local society” chapter of the book that made him yet more famous outside sociology, The Power Elite. Lazarsfeld thought Mills, in using the Decatur material for these books, was repaying his debts to the Bureau in scorn and contempt. In retrospect, the originating dinner in New York, that seven-hour marathon discussion in January 1945, was the best time they had together. For the dispute twisted into ugly personal shapes, produced volumes of emotion and ideas as each man pressed his claim.

Mills lost little time striking back. In a stream of essays written as he made his exit from the Bureau (and indeed from collaborative work altogether) he criticized the kind of administrative research he had undertaken in Decatur. “IBM plus Reality plus Humanism = Sociology,” the title of an essay published in The Saturday Review, more or less summed up the point. That he had Lazarsfeld in his sights nobody could question. Another of his essays was a rewrite of the address he had given in Boston in 1946; this time, it made Lazarsfeld’s book The People’s Choice the villain. One can catch the tone of these essays shifting from extenuation, to criticism, then breaking into competitive action. “On Intellectual Craftsmanship,” a primer on social research Mills composed in 1952, advocated sociology as a way of life, as a means of transcending the split between science and poetry. By the time Mills handed out his primer to his students at Columbia, White Collar had become a bestseller. He wished for the book to be read as a set of “prose poems.”

Lazarsfeld thought it was “a very dumb book.” As Mills pursued his independent public, Lazarsfeld pursued his style of research at Columbia. What progress he made! Although the Bureau of Applied Social Research never received more than 10 percent of its funding from the university, Lazarsfeld won virtually every moral and intellectual battle he waged. The Bureau moved to 117th Street, near the campus, and employed approximately one hundred staff members. Even its critics knew it was the most important center of quantitative social research in the country. They knew it because Lazarsfeld was busily teaching a whole generation of sociology graduate students how to reproduce the methods featured in The People’s Choice and Personal Influence.

Either Lazarsfeld or Merton held the title of “executive officer” of the Columbia graduate department since 1949. Either way, a strict professional ethos set in place. Sociology at Columbia was not a way of life or a means of transcending science and poetry. It was a technical discipline. Lazarsfeld thought White Collar was “a very dumb book” because it mixed up the analytic and the impressionistic. Merton was more flexible and searching than Lazarsfeld in his vision of sociology, yet he too expected it to evolve into a science. When an assistant professor of sociology published a film review in a New York newspaper, he was summoned to the office. Did he wish to continue teaching in the department? “Well, both Merton and I hope that this movie review you wrote is the last one; that it is not the kind of sociology you plan to practice,” Lazarsfeld said, adding under his breath, “The last thing we need is another C. Wright Mills.”

Young intellectuals in every industrial society in the world did what Columbia’s graduate students and assistant professors were not permitted to do, namely, discuss and debate Mills’s books. By the end of the decade, translations appeared in Argentina, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Spain, and the Soviet Union. Lazarsfeld found that whenever he went to Europe to lecture, somebody in the audience asked him about the author of The Power Elite. Why didn’t more sociologists write such interesting books? Asked this in Warsaw, Lazarsfeld exploded with a denunciation so caustic it embarrassed his hosts. Zygmunt Bauman witnessed the occasion: “Mills baiting was a favorite pastime among the most distinguished members of American academe: there were no expedients, however dishonest, which the ringleaders of the hue-and-cry would consider below their dignity and to which they would not stoop.”

Mills did not exactly elevate the tone of the dispute. The Sociological Imagination (1959) renewed the criticisms he had laid away in his essays of the early 1950s, now elaborated into a sustained attack against the schools and sects of academic sociology. The profession, Mills charged, was in the grip of “grand theory” and “abstracted empiricism”; the first tendency he charged to Talcott Parsons, the second, to Lazarsfeld. “As practices, they may be understood as insuring that we do not learn too much about man and society—the first by formal and cloudy obscurantism, the second by formal and empty ingenuity.”

No single set of propositions or problems could be said to characterize Lazarsfeld’s “abstracted empiricism,” Mills said. Although Lazarsfeld had carried out a great number of studies of public opinion since the publication of The People’s Choice, the results of these studies added no new ideas to the field. Their real subject was the perfection of method and the production of sociologists as technicians. If Lazarsfeld managed to institutionalize his administrative style over the long haul, sociologists would become state functionaries, their capital-intensive projects dependent upon corporate monopolies to introduce their questions and problems, their mental life given over to measurement at the expense of thinking. “The details, no matter how numerous, do not convince us of anything worth having convictions about.”

These observations and criticisms Mills drew directly out of his experience in Decatur. A casual reader would not have known this, for although he made Lazarsfeld the central figure in the chapter, he did not mention Personal Influence by name. Surely, he kept the project at the front of his mind. After all, he criticized authors who added a “literature of the problem” section to empirical data. This practice, he said, allowed casual readers to assume that the data had been shaped by theory, even when the data had come first and the “literature of the problem” had been added at the end to emboss the known results. Then there was the passage where he said the trouble with Lazarsfeld’s method was not only that it generated a great number of trivial truths.

If you have ever seriously studied, for a year or two, some thousand hour-long interviews, carefully coded and punched, you will have begun to see how very malleable the realm of ‘fact’ may really be.

The Sociological Imagination envisioned a social inquiry ranged around shared ethical convictions, rather than around a special set of techniques or a science of concepts. For Mills, these convictions bespoke freedom and reason as paramount values in human affairs. What is most important to grasp, though, is that his interpretation of social inquiry did not forsake fact-consciousness; Mills called for “a much broader style of empiricism.” Nor did it necessarily entail any particular political position. Mills’s list of forerunners and exemplars included John Kenneth Galbraith, Johan Huizinga, Harold Lasswell, Robert Lynd, Karl Mannheim, Gunnar Myrdal, David Riesman, Joseph Schumpeter, George Simmel, Arnold Toynbee, Max Weber, and William H. Whyte.

Nor was Mills alone in his distaste for Lazarsfeld’s methodology. In Fads and Foibles in Modern Sociology, Pitirim Sorokin blamed Lazarsfeld for an “epidemic of quantophrenia,” and earned for his effort a letter of commendation from Mills. Of the Bureau’s influence in sociology, the German émigré Hans Speier said, “certain analytical methods were refined, but the substantive questions that were being asked became shallower. Interest in the structure of modern society faded along with the interest in the fate of man in that society. As the techniques of interviewing became increasingly standardized, the art of conversation, which also provides civilized access to the life of the mind, deteriorated.”

In Western freethinking there has been a consistent tendency to charge concept-mongering and fact-grubbing as twin villains in the crime of unreality. There has been, moreover, a tendency to view methodology as a science of mental estrangement, a form of ascetic self-annihilation. “I mistrust all systematizers and avoid them,” Nietzsche wrote in Twilight of the Idols. “The will to a system is a lack of integrity.” In the United States, Mills’s protest against “methodological inhibition” goes at least as far back as the nineteenth-century academies and their bids for ecclesiastical guardianship over social knowledge. Emerson wrote:

It is plain that there are two classes in our educated community: first, those who confine themselves to the facts in their consciousness; and secondly, those who superadd sundry propositions. The aim of a true teacher now would be to bring men back to a true trust in God and destroy before their eyes these idolatrous propositions: to teach the doctrine of the perpetual revelation.

Substitute “sociological imagination” for God in Emerson’s commandment and you have the leitmotif of Mills’s dissent.

The stricter the technical establishment of mind, the more elaborate the bureaucracy, the greater the seduction of anti-politics, the better the chance for misuse and exploitation. In Science of Coercion, Christopher Simpson has produced some evidence that appears to warrant the chain of logic. Simpson’s evidence patches in the gap between December 1950, the last month Mills mentioned the Decatur project in his correspondence, and the publication five years later of Personal Influence.

According to Simpson, the Bureau of Applied Social Research received as much as 75 percent of its funding in this period from military and government propaganda agencies. The bare fact of state patronage, of course, says little in itself about the dispute between Mills and Lazarsfeld. They agreed that the Bureau’s empirical methodology could aid in the study of propaganda. (Mills himself had won one of the Bureau’s largest government contracts, from the Office of Naval Research.) Mostly, they differed on the ethical responsibilities of the inquirer. Here the matter grows curiouser. As Simpson observes, the State Department put the Bureau’s “personal influence” methods at center of its “psychological warfare” operations campaigns in the Middle East and Philippines. Lazarsfeld wrote the questions himself.

Mills opposed the American attempt to prop up the decaying British and French empires, and said so in his books. Lazarsfeld did not oppose the attempt, or if he did oppose it, he did not say so publicly, which amounted to the same thing. If this difference seems to be a mere historical fact, consider what the American attempt managed to accomplish. In 1953, military intelligence toppled the democratically elected prime minister of Iran, Mohammad Mossadegh. The CIA controlled the “opinion leaders” in the Tehran press almost completely.

What was the connection between “personal influence,” psychological warfare, opinion management, and the Middle East? Before Mills, these kinds of questions were taboo in academic sociology. For graduate students and assistant professors on the margins of the profession, The Sociological Imagination was a source of wonder and liberation. But the official organs and leading representatives of sociology angrily rejected the book and the author. Edward Shils, whose writings on the “primary-group” supplied a theoretical armature for Personal Influence, rapped Mills on the knuckles in a nasty pair of essays. Lewis Coser reproached him in Partisan Review. Seymour Martin Lipset and Neil Smelser issued a declaration of his nonexistence in the British Journal of Sociology. In a speech in Stresa, Italy, Robert Merton referred to (but did not name) a “little book by C. Wright Mills” as one of the “violent attacks” strafing sociology.

The only public response Paul Lazarsfeld made to the book showed up at the end of a forward to a monograph about college students. There he claimed (apparently without intending any irony) that Mills promoted “a kind of sophisticated commercialism.” In truth, Lazarsfeld did not know what to make of The Sociological Imagination, and he could not avoid thinking about it either. In an interview he disburdened himself of his feeling of agitated confusion. “I find what Mills writes, you see, just ridiculous. There is nothing in the world he can, as a research man, contribute to anything, by what he’s writing about, power or whatever it is and how bad the world is and so on. Why does he mix it up? I mean, why doesn’t he leave us alone?”

In the spring 1961, the International Sociological Association (ISA) was planning for its next World Congress. The Congress was coming to Washington, D.C., which meant that a joint meeting was going to be held with the American Sociological Association (ASA). Lazarsfeld, as president of the ASA, was going to chair the keynote panel, which was going to feature two American speakers. Probably nothing unusual would have happened if he had answered his mail. For the chair of the ISA’s program committee sent him several letters asking for candidates for the keynote panel. The chair did not receive an answer, and as there was already some confusion concerning jurisdiction over the joint session, he went ahead and found a speaker on his own.

Mills accepted right away. Lazarsfeld was flabbergasted. “I obviously don’t want to bring such matters up with the International Organization,” he wrote to Talcott Parsons. “This letter is addressed to you as the ranking permanent officer of the American Association. I am sure you will find a way to cope with the problem.” Parsons concurred that the invitation to Mills was “extremely unfortunate.” He would make some inquiries. “If it seems clear that this invitation was issued without any real clearing from the Association, I shall write a strong letter of protest.”

Parsons raised “the problem” during a meeting of the ASA’s Committee on Organization and Plans in New York and enlisted the aid of Seymour Martin Lipset. Lipset and Lazarsfeld met in London with the chair of the ISA’s program committee. They exerted the academic equivalent of diplomatic pressure.

The letters exchanged on “the problem” conveyed no speculations as to what Mills might talk about, should the invitation stand. Nor did they betray any qualms in conspiring against the world’s most widely read American sociologist at the world’s most prominent sociology congress. So far as the letters showed, Lazarsfeld, Parsons, and Lipset were unanimous in their desire to deprive Mills of his right to speak. They wished only to do so “without embarrassment” to the ASA, as Lipset stipulated. This they achieved. The ISA rescinded the invitation. Because the ISA explained its decision to Mills on a false pretext suggested by Lipset, there was a chance the stratagem could collapse. “If Mills should insist on coming, I do not know what we can do,” Lipset wrote. But by the middle of July 1961, with no sign of trouble in view, Parsons relaxed. “I gather that the whole thing is now worked out and it will be one of the senior American ‘organization men’ who will do it.”

Mills died the next year of a heart attack at age forty-five. Lazarsfeld and Merton, the men who urged him to New York in 1945, declined an invitation to attend his campus memorial service. Lazarsfeld refused even to write his widow a note of sympathy. It was not that he overlooked these gestures. “I absolutely refused even after his death to have anything to do with him,” he said. “That is to say, I never regretted whatever harm I might have done. You see, I had the absolutely opposite feeling. Not only did I not regret … but I made it an external point not to take the slightest notice of whether he was dead or not.”

At least Lazarsfeld did not indulge any facile talk about the tragedy of it all. Perhaps he knew that without a genuine possibility of success, there can be no tragedy. Perhaps someone had finally told him that, back in graduate school, Mills had flunked statistics.