Are you a white supremacist?

Are you sure?

“We have for the last few years the most diverse Sepac board that has ever existed in the city of Cambridge, and to have somebody come in and pull a power play that feels very white supremacist …”

This malediction rocked a January 22 public meeting of the Cambridge Special Education Parents Advisory Council (Sepac). Me, a white supremacist? I had merely filed an Open Meeting Law complaint against the Cambridge Sepac’s board, accusing its members of neglecting to give notice of their meetings and to hold elections for more than a year. The meeting, convened to discuss my complaint, started off with the malediction.

Since its passage in 2010, the Open Meeting Law has become an important, if modest, mechanism available to anyone in Massachusetts — even a moneyless single father of a severely disabled son — who asks for greater democracy in representative associations. I didn’t expect the Sepac’s current board to embrace me, especially since I had called for their resignation in a December letter in the Cambridge Day, a local rag. Still, I expected the process could facilitate a discussion of my two-page complaint, one of many received every month by the attorney general against municipal zoning boards, city councils, conservation commissions, school committees, and other “public bodies” suspected of deliberating in secret.

I thought about the history of American white supremacy, which emerged as a conscious identity in 1866, when ex-Confederates in Tennessee formed the Ku Klux Klan to crusade against Reconstruction. In the 1920s, the KKK rally three million members to the cause of “native, white, Protestant supremacy.” White Citizen’s Councils blighted the South after “Brown versus Board of Education,” the Supreme Court’s 1954 school integration ruling. “Unite the Right,” the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, proved the abomination is not nearly done with us.

After I heaved a defensive belly laugh, I asked my accuser what in the world white supremacy’s long reign of murder, arson, hatred, and nihilism had to do with me. “I didn’t call you that,” she said, interrupting my objection. “I said the action was that.”

This casuistry deepened the mystery. My accuser seemed to imply that a nonwhite person wouldn’t have incurred the slur because no nonwhite person would have dared to complain about “the most diverse Sepac board that has ever existed in the city of Cambridge” in the first place. The reasoning slipped into syllogism. All whites are supremacists. I am white. All whites are supremacists. Therefore, my request for greater democracy in Sepac makes me complicit in an ideology I’ve always despised. My guilt was a simple matter of deduction.

I waited for someone to speak up against the logic of guilt by association. Sepac is a small group of parent volunteers brought together to advocate for special education, but the 20 or so participants in this meeting also included the district’s lead attorney, the executive director of special education, and two members of the Cambridge School Committee. None breathed a word in my defense.

I can see why, since collective white guilt is a core doctrine in the Cambridge Public Schools. Back in 2011, when Silicon Valley was liberal, our administration and the school committee sought to close the “racial achievement gap” by adopting an Innovation Agenda that did not mention diversity. But the language and prominence of race soon inflated dramatically, as liberal media turned America’s heterogeneous composition into a dichotomy between “whites” and “communities of color.” Instances of the term “white supremacy” in The Washington Post and The New York Times multiplied by 1,800 percent between 2014 and 2019.

That year, graduates of the Harvard School of Education introduced critical race theory to Cambridge through a new strategic initiative. Building Equity Bridges located “a culture of white supremacy” at the root of “barriers to equity” in the district. Suddenly discovering the specter of tiki torches lurking from the classrooms to the broom closets, the administration instituted mandatory DEI staff training, created an office for racial equity, circulated guidelines “to counter the dominant narrative of straight, white men as the makers of history,” and overhauled the curriculum. The Cambridge teachers’ union distributed a questionnaire to candidates in the school committee election: “How will you address racial inequities and white supremacy culture in our schools and district?”

How indeed? Collective guilt is a superstition, a secular analogue of original sin. The doctrine dangles the possibility of vicarious redemption to “good whites” such as my accuser — the only white member of the Sepac board — willing to “do the work” of atonement. Rather than saving Black people, the good white person saves herself. The district promoted the salvation gospel in Robin DeAngelo’s “White Fragility,” Nikole Hannah-Jones’s “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story,” and Ibram X. Kendi’s “Stamped From the Beginning.” Building Equity Bridges took a quotation from Kendi as its motto: “Even inaction (simply being ‘not racist’) in the face of racism is, in fact, a form of racism.”

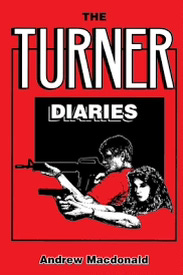

The doctrine, so conceived, shifts the predicate from a testable notion that racist attitudes are held by culture to a non-falsifiable assertion that racism originates there. When acting racist is conflated with being racist or having racism, the phenomenon resists contingency, volition, and perspective, the normal features of inquiry. Evacuated of skepticism, the tribal conception of racial belonging may lead adherents to embrace their fate rather than atone for it. “The fact is that we are all responsible, as individuals, for the morals and the behavior of our race as a whole. There is no avoiding that responsibility, and each of us individually must be prepared to be called to account for that responsibility at any time.” That’s from “The Turner Diaries,” the 1978 novel of racial apocalypse popular with (actual) white supremacists. If white supremacy is both ubiquitous and ineradicable, then individuals have no meaningful choice. If all whites are guilty, then no whites are guilty.

“This work will never be ‘complete,’” promised the architects of Building Equity Bridges in 2019. A project that by definition cannot be completed is one that cannot succeed, either. Cambridge today spends on its students twice the state’s average and yet has a “racial achievement gap” that is worse than the state average.

Inevitably, the compulsory practice of a dogma, whether it claims to represent The One True Church, American Patriotism, or Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, congeals into orthodoxy. An orthodoxy that combines self-righteousness with self-pity loses the capacity to know the difference between criticism and persecution.

Thus, if I had loosed so much as a syllable with the faintest racial overtones, the meeting’s participants would have rent their garments and raised a cry to heaven. As it happened, my disobliging posture toward the Sepac board’s attempt to change the subject made a discussion of my complaint inconceivable. A minor grievance over democratic procedure magically transformed into a supposed attack on diversity itself.

When I exclaimed, “You’re supposed to have elections, for God’s sake,” a board member quailed that I “took the Lord’s name in vain.” When I said “disabled child,” another spoke of “a child of different abilities.” When I said the white supremacy accusation sounded “dumb,” the chair scolded: “The language you are using can be quite harmful.” Nobody said so, but my maleness must have redoubled the malignancy of my whiteness. “The most diverse Sepac board that has ever existed in the city of Cambridge” had no men.

My Open Meeting Law complaint is still pending. President Trump, meanwhile, has evinced neither the slowness of bureaucratic procedure nor the inhibition that silenced my witnesses. His Jan. 29 executive order repealed federal support for education policies predicated on collective guilt: No individual “should feel guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress because of . . . actions committed in the past by other members of the same race.” Progressives who spent the last decade drumming up scapegoats, invigilating speech, and proving the malleability of institutional norms have themselves to blame for holding open the door.

The historian Russell Jacoby, one of many commentators who predicted the “self-immolation” of progressives, in 2022 summed up their penchant for demagogy this way: “If you question diversity mania, you support Western imperialism. Wonder about the significance of microaggression? You are a microaggressor. Have doubts about an eternal, all-inclusive white supremacy? You benefit from white privilege. Skeptical about new pronouns? You abet the suicide of adolescents.” Now we are all paying the price of bullying by buzzword.

“The strength of being offended, as a state of mind, lies in not doubting itself,” J.M. Coetzee wrote in “Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship.” “Its weakness lies in not being able to afford doubt itself.” Everyone deserves an equal benefit of the doubt. No one utterance contains a total system of values. Rather than forestalling the anxieties of difference with brittle racial certainties, progressives should relearn how to risk democratic conversation.

The alternative is a future of isolation and mistrust. “We’re very happy to work with you,” my accuser offered at the end of the meeting. No, thank you.